“What’s a good night for Dave to come over for Vinyl Night?” I asked my wife Sandy recently.

She rolled her eyes magnificently and exclaimed “Vinyl Night? There is no good night for Vinyl Night!”

And why did she say that? Because when my excellent pal Dave comes over for Vinyl Night, as he does once or twice a year, we listen to a genre of music that Sandy, to say the least, hates. “I don’t consider it to be music,” she explained to me succinctly during dinner not long ago. Understood.

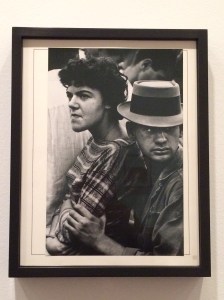

And you know what? Boatloads of people would agree with her, but they can’t, because most folks have never experienced this kind of music. Don’t know that it exists. Here’s what I’m talking about: On Vinyl Nights, Dave and I gorge on jazz of the avant-garde variety. The wild and aggressive type in which melody often is minimal and screeching horns and thrashing drums are the norm. The type that might well be described as seismic in quality and in effect, as will become apparent.

Free jazz. That’s the name that has stuck to this fringe music which began to emerge in the mid-1950s. And liberating it is. The musicians are free to roam far and wide. And the music opens the minds and loosens the emotional chains of those listeners who like it, such as Dave and I, tossing us around like hold-on-for-your-lives roller coaster riders.

Sandy relented and Dave ended up coming over on a Wednesday night, because that was when she had plans to watch a lot of prime time television in the upstairs bedroom. Dave and I, in the living room, would be free to crank up the stereo system’s volume as high as we might. Turns out that wasn’t a good idea.

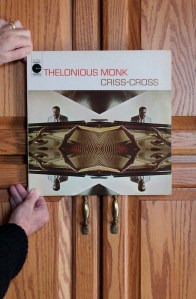

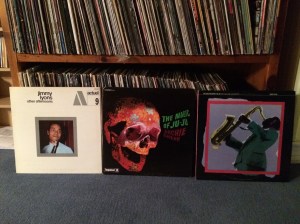

In preparation for each Vinyl Night I head to the basement room where my most prized possession resides: my vinyl album collection. I’ve got a ton of albums. Lots of musical styles. Never got rid of any of them, one of the smart calls I’ve made in life. On the afternoon of this most recent occasion I walked to the shelves holding the discs and made the selections for that evening’s Vinyl Night. Albums by Jimmy Lyons, Roswell Rudd, Grachan Moncur III, Art Ensemble Of Chicago, Archie Shepp, John Carter/Bobby Bradford, and Albert Ayler. Household names, no? As always, Dave and I would listen to one side of each album.

Dave arrived around 8:00 PM. Sandy gave him a hug and walked upstairs, not to be seen again for a couple of hours. I placed side one of Jimmy Lyons’ Other Afternoons (recorded in 1969) on the turntable and an evening of fun, then mayhem, began. Jimmy Lyons no longer is with us, but his recordings live on with force. And force is what soon blew through the stereo speakers in my living room. The title track, Other Afternoons, began calmly enough. Didn’t take long however for alto saxophonist Lyons and his cohorts to wail and fly as though demons were on their tails and gaining fast (click here to listen). That’s when Dave and I thought we heard the sounds of wood and plaster creaking a bit more than they should in an old house. We put those thoughts out of our minds.

Several albums later a firestorm hit the turntable, Archie Shepp’s The Magic Of Ju-Ju (recorded in 1967). The title song, occupying all of side one, made Other Afternoons sound like a wimp. Shepp, whose career began in the early 1960s and who is alive and kicking, hit the ground at Usain Bolt speed, screaming on his tenor saxophone for 18 minutes over a drumming cacophony (click here to listen). I was amazed, mesmerized and kind of in a daze. Dave too. That’s the power of Shepp. We definitely heard those creaking sounds again, some rumbling ones also, but put them out of our minds.

The problems became undeniable a couple of albums after Shepp’s. Tenorman Albert Ayler, long gone, went stratospheric at around the six minute mark of Spirits Rejoice (recorded in 1966), which takes up all of side three on The Village Concerts double album (click here to listen). My house couldn’t take it any longer. Plaster started falling from the living room ceiling. The living room floorboards began to buckle and give way. Good things weren’t happening upstairs either. Sandy came running down the stairs. “I really, really hate this music,” she yelled as she and I and Dave bolted out the front door. We stood in disbelief on the sidewalk as Sandy’s and my suburban home dropped to the ground. The house’s descent took a long time and was extremely jarring, just like the saxophone, trumpet and other instrumental solos that Dave and I grooved to on that most infamous of Vinyl Nights.

The next day I called my Allstate agent. I described the bizarre situation to her. She said, “You’re out of luck, Neil. Your homeowners policy specifically prohibits you from playing any free jazz above the 80-decibel level. Allstate isn’t going to pay you a cent. We may be the ‘you’re in good hands’ people, like our logo says, but we’re not fools like you!”

(If you enjoyed this article, don’t be shy about sharing it. Sharing buttons are below)